This blog highlights interesting items from the Sturgis Library Archives. Today’s highlight is a document that dates to the resistance movement that immediately preceded the Revolutionary War.

MS. 75: Historic Documents Collection

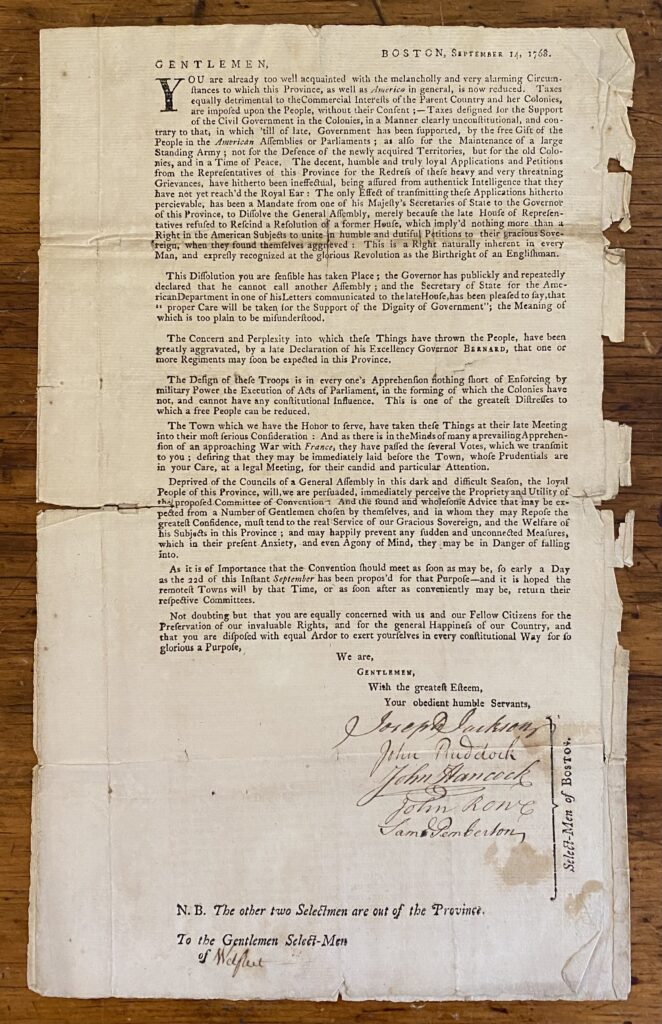

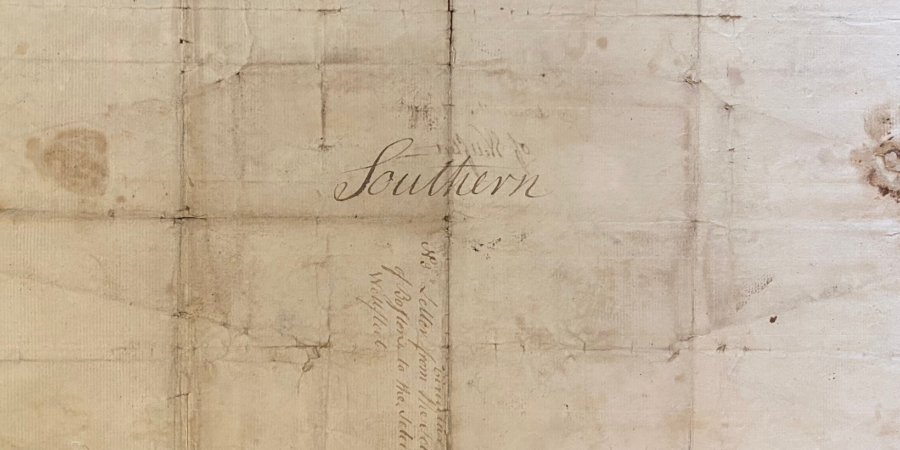

In September 1768, the selectmen of Boston sent a letter printed in broadside format to the selectmen of each town in Massachusetts. The copy housed in Sturgis Library’s archives is addressed to “the Gentlemen Select-Men of Welfleet.”

This letter implored towns to send delegates to a week-long unauthorized convention in Boston. The convention aimed to address the colonists’ various constitutional grievances on the eve of the landing of British troops in the city. To the selectmen of Boston, the impending arrival of British troops represented an alarming escalation of tensions between the colonists and the mother country.

These tensions stemmed from actions taken by the British Crown to raise revenue and assert more control over the colonies in the wake of the Anglo-French Wars, specifically the French and Indian War (1754-1763). Britain sought to pay down the war debt it incurred defending the colonies in the French and Indian War by levying new taxes and strengthening the enforcement of existing tax laws. Each time the British parliament passed new acts in an effort to extract more revenue from the colonies or to assert more control over provincial affairs, the colonists resisted in multiple ways.

In February of 1768 the Massachusetts House of Representatives responded to the Townshend Acts by sending a circular letter authored by Samuel Adams and West Barnstable’s own James Otis Jr. to the representative bodies of the other colonies. This letter denounced the Townshend Acts for being unconstitutional “taxation without representation” and advocated for a return to the system where local assemblies controlled taxation. The Crown’s Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Hillsborough ordered the House to rescind the letter but they voted against doing so. As a result, Governor Francis Bernard dissolved the Massachusetts general assembly which further enraged the colonists and lead to rioting.

One such riot occurred on June 10, 1768 after customs officials seized John Hancock’s ship Liberty for violating trade acts. Rather than serving as an example of Royal authority, the event sparked “one of the fiercest riots in Boston’s history.” In response to the mob violence, British authorities ordered two regiments of troops to quarter in Boston to maintain order. By September, news of British troops coming to police the colonies alarmed many colonists and prompted the letter from the selectmen of Boston to the selectmen of Massachusetts towns.

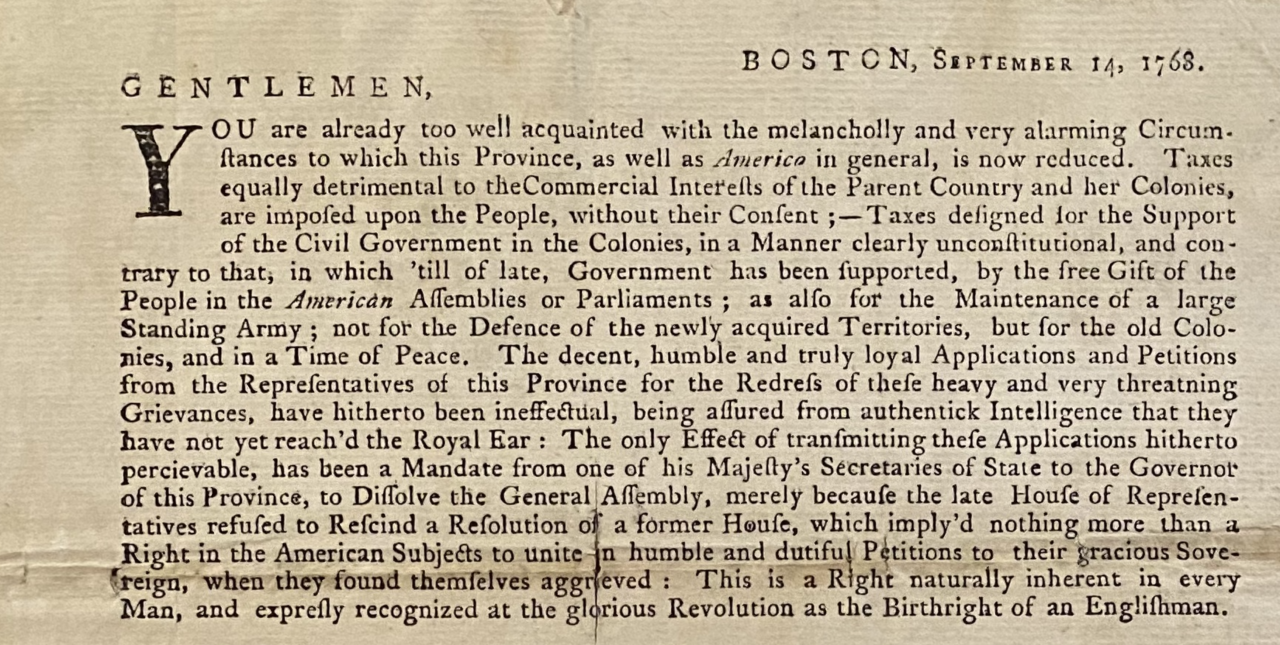

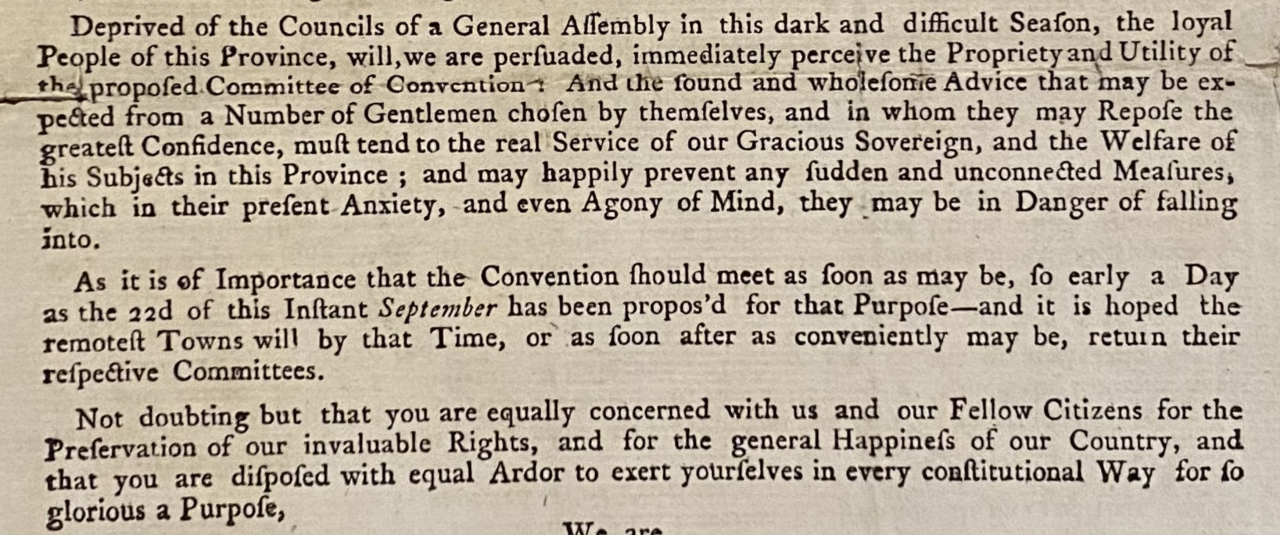

In the first paragraph of the letter, the authors outline “the melancholy and very alarming Circumstances to which this Province, as well as America in general, is now reduced.” They condemn “taxes equally detrimental to the Commercial Interests of the Parent Country and her Colonies” as unconstitutional and go on to explain that their petitions for “these heavy and very threatening Grievances” have “not yet reach’d the Royal Ear.” They describe their previous attempts at redress including the authoring of the circular letter back in February as “decent, humble and truly loyal Applications and Petitions.” They assert that writing such a letter is a “Right in the American Subjects to unite in humble and dutiful Petitions to their gracious Sovereign, when they found themselves aggrieved.” A right they say was “expressly recognized at the glorious Revolution as the Birthright of an Englishmen.”

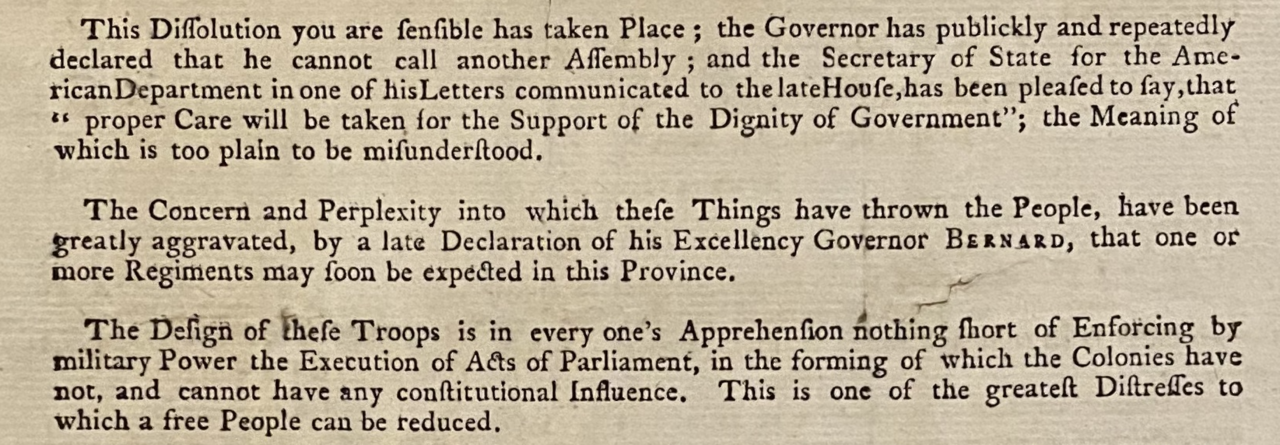

The following three paragraphs illustrate the deepening divide between the Crown’s representatives in Massachusetts and the colonists. First they mention the dissolution of the Massachusetts House of Representatives and then point out the governor’s refusal to reinstate the assembly as well as the secretary of state’s dismissal of their concerns. They go on to say that the “concern and perplexity” these issues cause “have been greatly aggravated, by a late Declaration of his Excellency Governor Bernard, that one or more Regiments may soon be expected in this Province.”

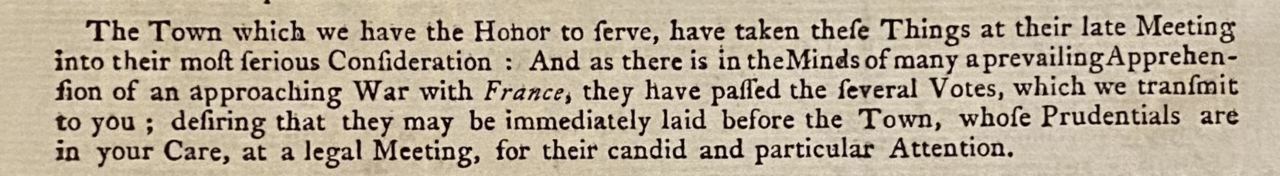

In the next paragraph, the selectmen claim that “there is in the Minds of many a prevailing Apprehension of an approaching War with France.” In The History of the Province of Massachusetts Bay from 1749-1774 historian Thomas Hutchinson argues that no one actually thought a war with France imminent. Rather, this was a pretense for colonists to furnish themselves with firearms as a sort of trial for how they would receive an open proposal for opposition. This also provided a pretext for the meeting that carried the weight of a war threat.

The last three paragraphs reiterate the importance of a meeting to discuss constitutional grievances and takes pains to show deference to the King. The authors claim that the delegates at the convention “must tend to the real Service of our Gracious Sovereign, and the Welfare of his Subjects,” which echoes deferential language earlier in the document that refer to the their “humble and dutiful Petitions to their gracious Sovereign.” This language can be seen as an attempt to insulate the authors from charges of sedition and also as an appeal to those colonists that might be far more loyal to the Crown than some of the selectmen of Boston.

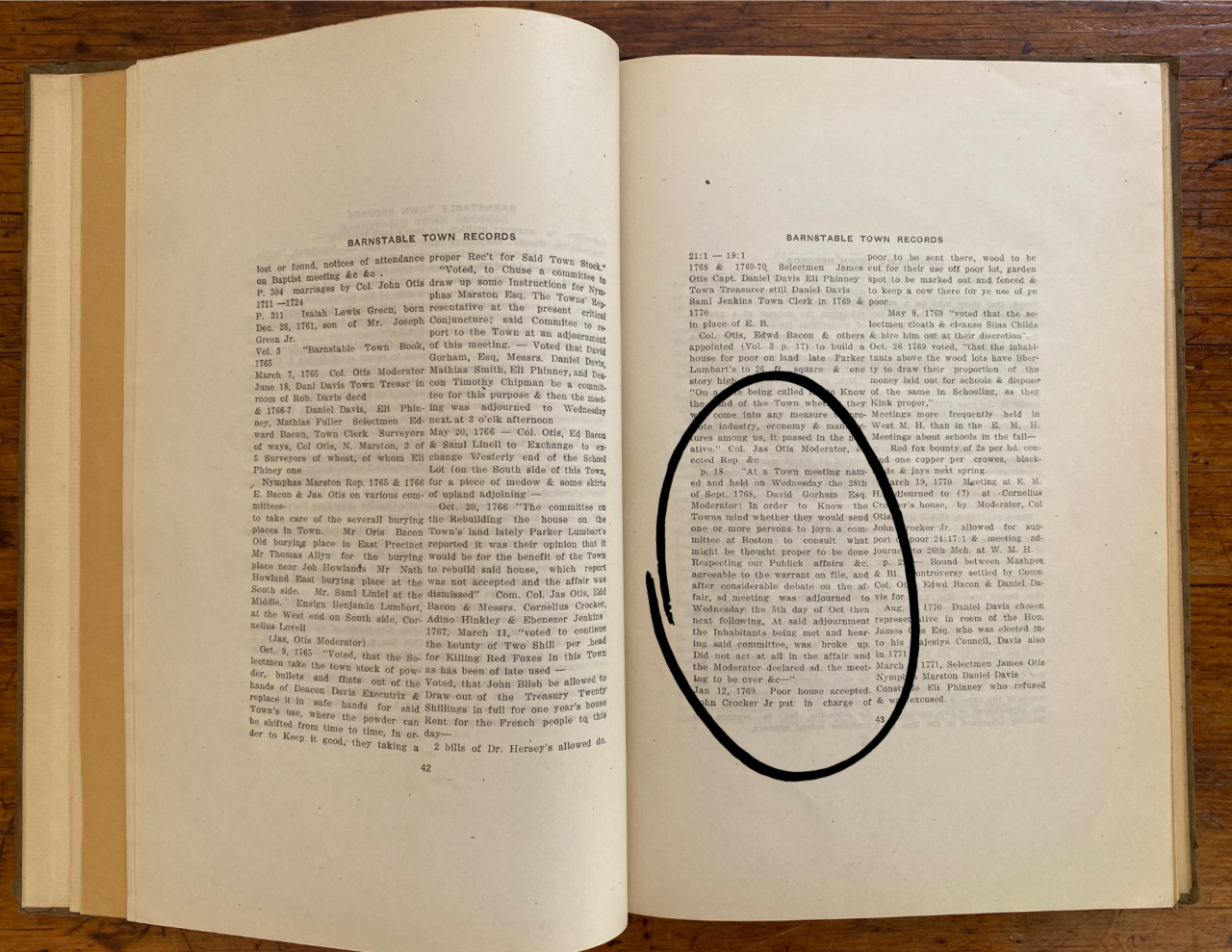

This document was written prior to full fledged Revolution. There remained a wide spectrum of perspectives about the proper balance of power between the Crown and his subjects. Many towns did not send delegates, either because they disagreed with the idea of an unlawful assembly not approved by the proper British authorities, or for a variety of other reasons including slow postal service or inability to fund the trip. Only two towns from Barnstable County sent delegates to the convention- Falmouth and Wellfleet. According to Barnstable town records, the politically divided town of Barnstable, delayed action on deciding to send a delegate until after the convention ended. This indicates that friends of the administration succeeded in blocking participation.

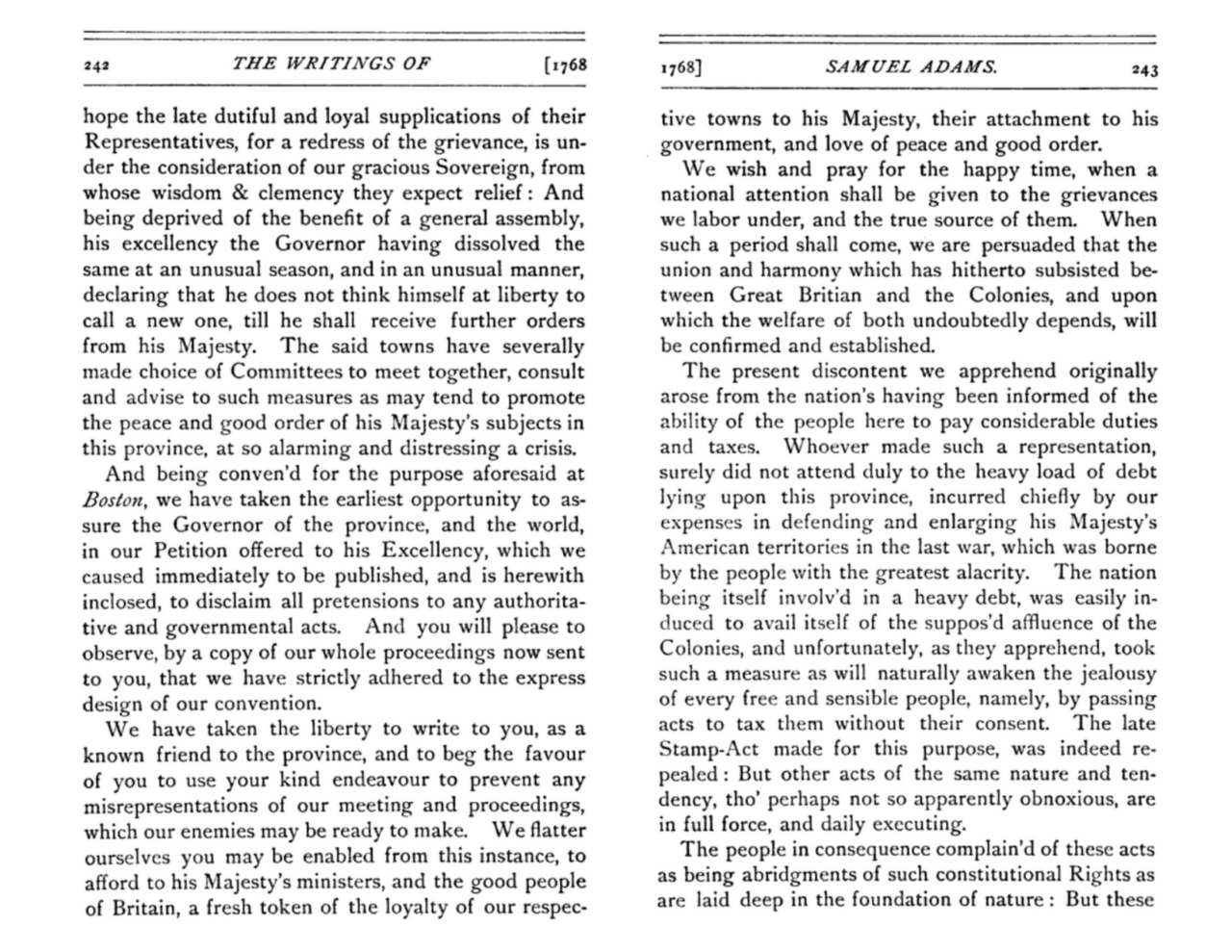

At the convention, more radical voices like Samuel Adams advocated for bold action while moderate voices called for conservative measures such as written petitions. In the end, the moderates won out and the convention drafted various letters to both reassure the British authorities of their loyalty and to request consideration for grievances. Below is part of a letter penned by Samuel Adams on behalf of the convention that demonstrates the placating tone the delegates struck when addressing British authority.

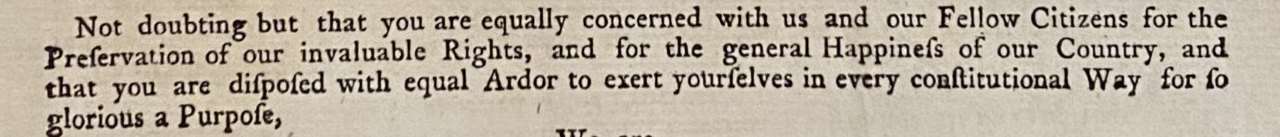

Despite their respectful tone, Governor Bernard firmly ordered the end of the convention deeming it illegal. The colonists persisted and finished out the convention but failed to stop British troops from arriving on their shores or effect any significant change. While the convention did not produce immediate tangible results, historian John C. Miller argues that “it was the precursor of the Massachusetts provincial congress and paved the way for linking together the towns of the colony under Boston’s guidance in the committees of correspondence.” Likewise, historian Thomas Hutchinson said the convention represented “a greater tendency towards a revolution in government, than any preceding measures in any of the colonies.” Certainly the precursor to Revolution can be felt in the language of the final paragraph of the letter from the selectmen of Boston with phrases like “invaluable Rights,” “general Happiness,” and “so glorious a Purpose.”

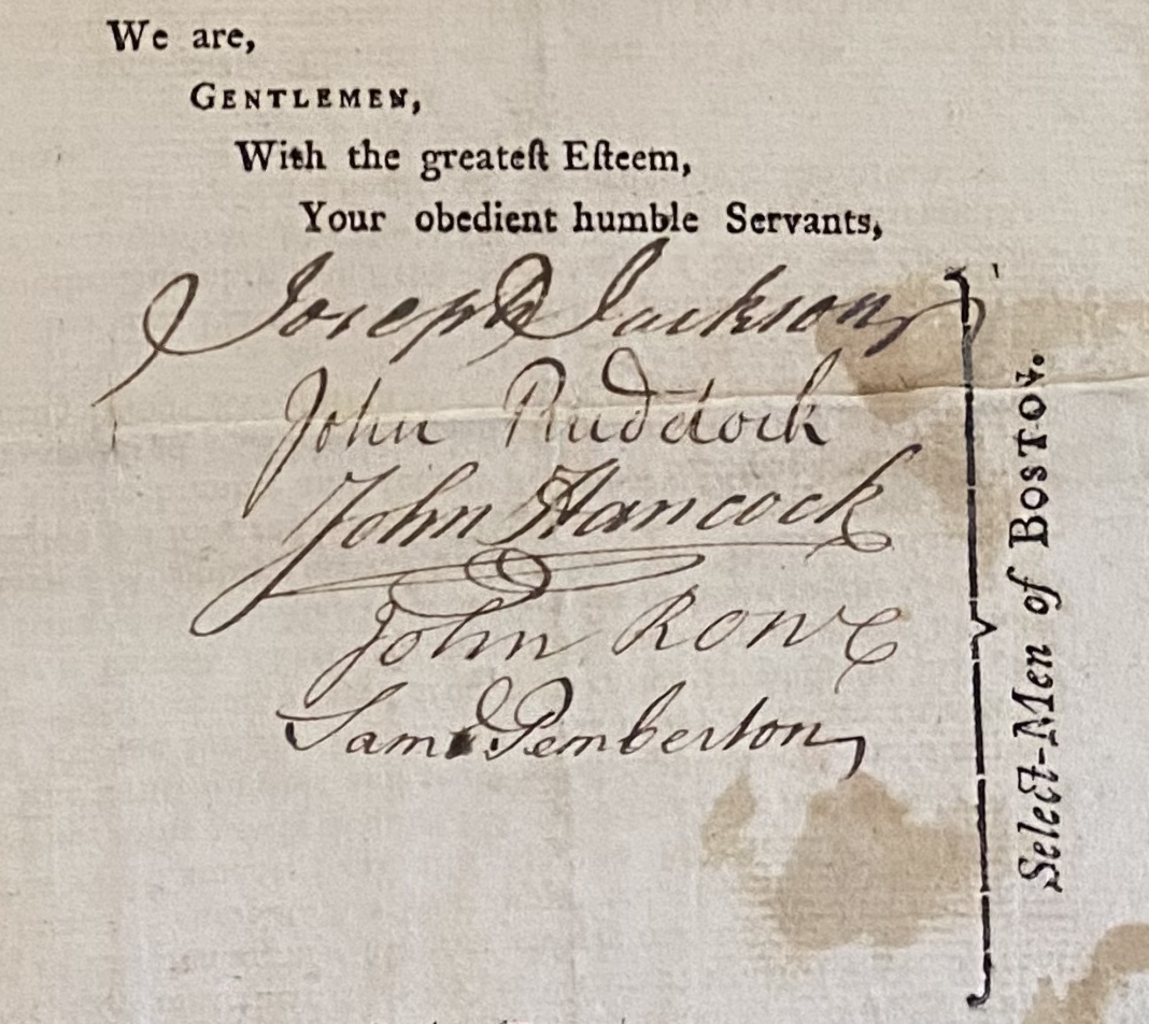

Perhaps one of the neatest features of this document is the signature of the first signer of the Declaration of Independence, John Hancock. As selectman of Boston during this period Hancock took an active role in the resistance movement that preceded the Revolution.

Sturgis Library’s extensive collection of research materials contains extremely rare and one-of-a-kind primary and secondary source material.

This document and other archival material are available for in-library use. To access archival collections contact us at director@sturgislibrary.org or call the Library directly at (508) 362-6636.

To see the findings aids for our archival collections, click here.

You can search the archives by name and subject using the CLAMS online catalog.

Thank you for sharing such a fascinating story. I imagine this letter must have been quite a scandal in it’s time! It’s interesting to read this document having the benefit of knowing the long-term outcome of events… when read in 2022 it seems as though the “Gracious Sovereign” did in fact have justified cause for alarm despite the colonists attempts to show deference!